"Deterrence of Aggression": Implications of New Aleppo Offensive

The state of play after one day

The nearly four-year “ceasefire” freezing the frontlines around northwest collapsed on the morning of November 27, 2024. Syrian opposition fighters under the Fatah Mubin Joint Operations Room (FM) launched a wide-ranging offensive against regime positions along the western Aleppo front, quickly capturing more than a dozen towns and pushing to within a few kilometers of Aleppo city. The offensive followed years of back and forth skirmishes and attacks between the two sides. In December 2022 members of Fatah Mubin conducted the first cross-line raid against a regime position in southern Idlib. Since then, the opposition has conducted these hit-and-run style raids off and on across the Greater Idlib frontline, seizing a defined regime position on the edge of no-man’s land, detonating it, and withdrawing.

For its part, the regime has regularly shelled Idlib since the very beginning of the February 2020 “ceasefire” and Russian warplanes have routinely conducted heightened periods of bombing runs across civilian areas. More recently, the Russian military has begun supplying regime forces with an excessive amount of FPV and suicide drones - the same models used in Ukraine. These drones have completely changed the dynamic in Idlib, amplifying the regime’s ability to spread terror among civilians and strike small, mobile military units. Fatah Mubin has framed its current operation as a response to these regime and Russian escalatory attacks, the most recent of which left four children dead when regime forces shelled a school in Ariha.

Day 1

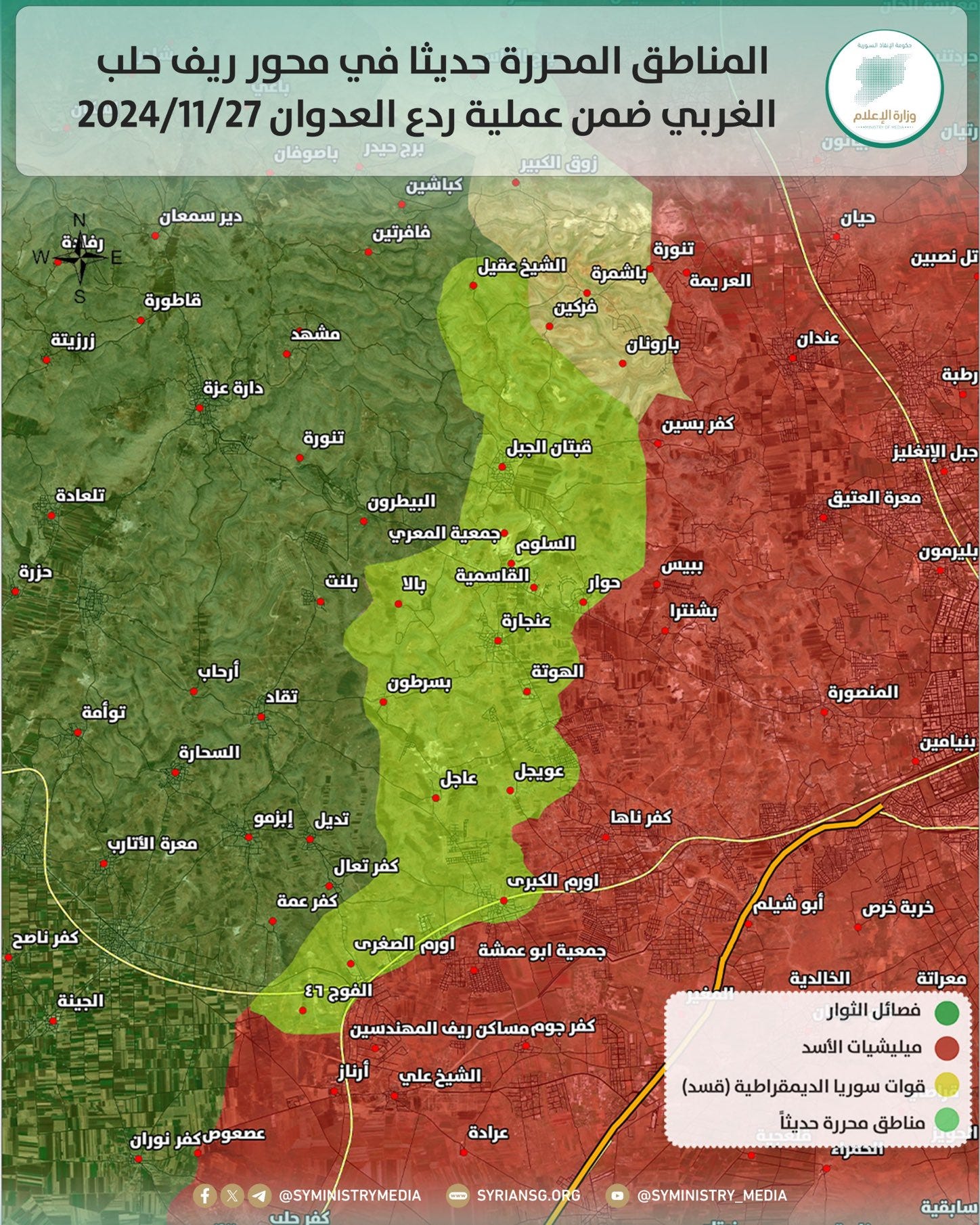

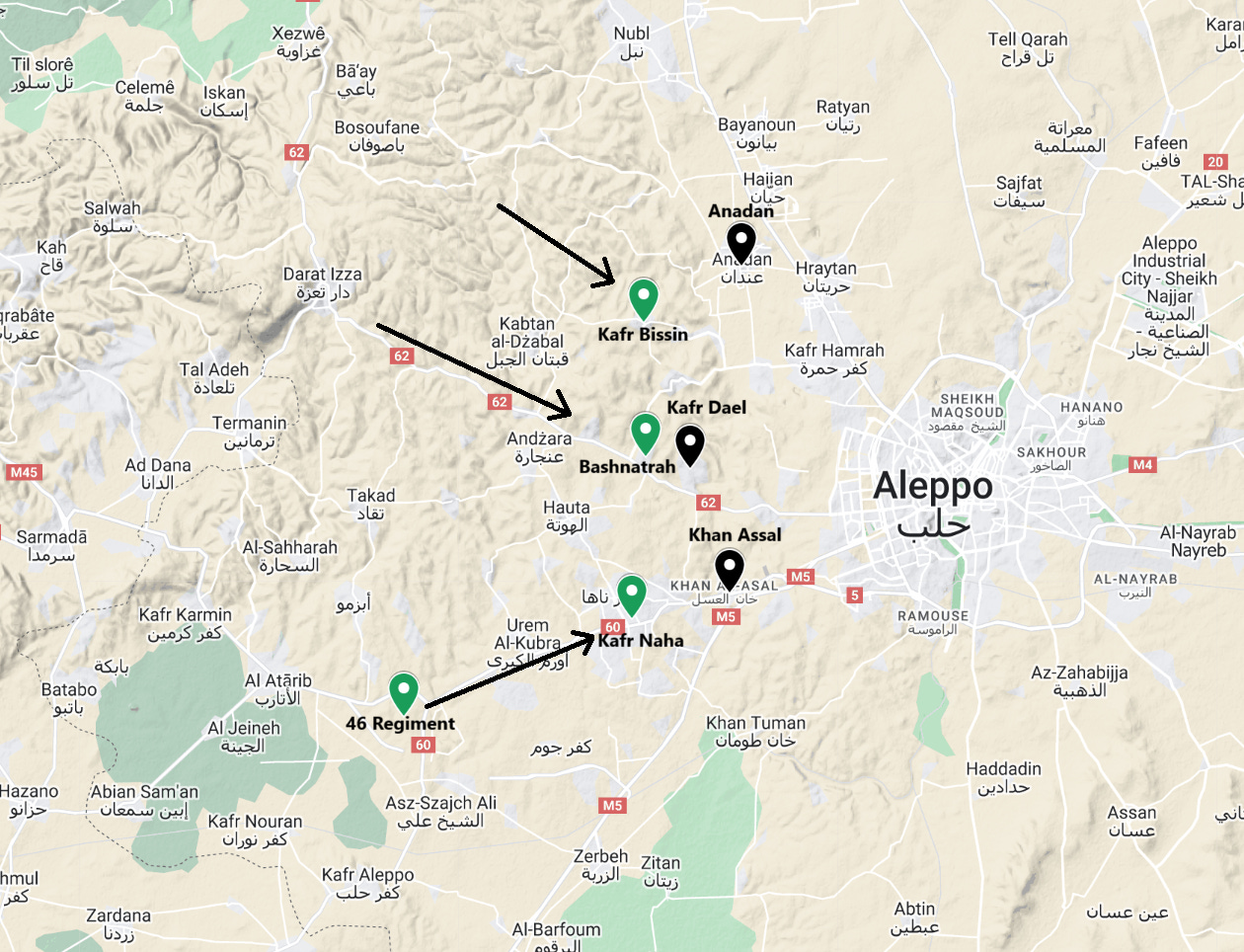

The operation began with a combined arms assault across multiple axes. FM pushed infantry forward in BMPs and their DIY armored personnel carriers, all supported by tanks while artillery and suicide drones prepped regime positions. First line units were quickly followed by mortar and ATGM crews who could set up on newly captured areas. The frontline appears to range from the Regiment 46 Base in the south to the Sheikh Aqil region in the north. This part of the west Aleppo front has seen none of the FM raids that became commonplace over the past two years. It also provides the only elevated approach to Aleppo city, as the land south of Regiment 46 is more defined by open farmland. This northern front also places the FM advance very close to the territory controlled by the other anti-Assad coalition, the Syrian National Army, and it Turkish military backer.

Video of FM suicide drone hitting regime position on the morning of November 27, posted by majd832250

In the south, FM forces pushed through the poultry farms on the northwest side of Regiment 46, quickly overwhelming the undermanned base. Credible reports have emerged that the attack began with a suicide car bomb against frontline regime positions, followed by the mechanized infantry push. No group has claimed responsibility for the bombing, and given HTS’s insistence on ending such practices after the battles in 2019 and 2020 it was likely the attack was conducted by one of the few semi-independent foreign factions remaining in Idlib. After clearing the base, opposition forces pushed through to Orem Saghir and Orem Khabir.

As sun set, some FM units continued eastward along Highway 60, with credible claims the opposition captured Kafr Naha around 9:00pm (Navvar Şaban claims the village was heavily IED’d and took extra time to sweep). Fighters on this front claimed the regime forces retreated all the way to Khan Assal, the last major fortified area outside of Aleppo city’s western neighborhoods. Regime forces likely hoped to regroup and organize a defensive position here, but reports suggest FM units began assaulting the town late at night on the 27th.

To the north, opposition forces quickly advanced to Qabtan al-Jabal and Hawar along the Highway 62 axis, with credible reports that Bashnatrah was liberated around the same time as Kafr Naha. These advances put the main regime defensive line early on November 28th at Anadan in the north, Kafr Dael in the center, and Khan Assal in the south.

Casualty estimates are still very early, but so far Trenton Schoenborn has documented at least 46 opposition fighters killed while I have found at least 33 regime deaths reported by pro-regime media. The regime losses include a colonel, three majors, and four captains, many of whom served in the 105th Brigade and 30th Divisions of the regime’s Republican Guard. Nearly all of the reported regime deaths so far come from core regime regions of Latakia, Tartous, Hama, and Homs. This means that we are likely seeing the commanders of platoons and companies stationed along the front, and the soldiers under them - many of whom are conscripts from more far-flung provinces - have not been reported yet in pro-regime media. Put simply, the high number of mid-rank officers among the documented dead suggests many more regime soldiers were killed (Liwa al-Quds - which has taken confirmed losses via pictures from the front - has not reported any of its dead yet as well). Opposition forces also managed to ambush and kill a group of Russian special forces soldiers and captured at least three tanks as well.

Implications

Why has this offensive been so successful so far? Fatah Mubin’s ability to generally keep the details of the attack secret has played a large role, and the group continues to show a much improved degree of operational security throughout this offensive than in years past. But the regime has also suffered manpower issues along this front, making it a prime target. The west Aleppo countryside is manned largely by elements of the 30th Republican Guard Division, a newer unit formed after the regime captured Aleppo city in 2016 and designed to bring a variety of pro-regime forces under a single command. However, pro-regime complaint pages have for many years complained about the widespread practice of ‘tafyish’ here - paying bribes to unit commanders for extended leave. This has caused many positions to be severely undermanned, as much of each deployed unit has actually paid their way back home. Undermanned, lower tier units caught off guard fled at the first sign of contact, many seem to have been killed, others captured. The regime, as usual, has relied on its artillery and air force to try and blunt the advance. Many of the opposition dead have been killed this way (though there are several pictures showing opposition infantry ambushed and killed during the attack as well).

All of this is to say that it has been less than 24 hours since northwest Syria’s first offensive in four years began. Rapid opposition advances are quite common, the difficulty always comes in the ensuing days as the advance slows and both sides dig in. The opposition cannot beat the regime in a war of attrition. It does not matter how much more skilled opposition fighters might be when the regime can call on tens of thousands of conscripts to push into a single front. Even in the best case scenario where FM units breach the Aleppo city suburbs, it is difficult to see how it does not become a repeat of the opposition’s failed 2016 attempt to lift the siege of Aleppo. Supply lines stretching from Idlib to the city are easy targets for Russian and Syria jets while the regime is able to send wave after wave of infantry at limited opposition resources.

This same pattern played out five years ago, when opposition fighters conducted a promising counter-attack in northwest Hama, re-capturing Hamamiyat and Tel Malah. Elite units hunkered down in these positions for weeks, repelling multiple regime pushes. Eventually the regime simply pounded the fortified positions with artillery for days on end, most of the fighters were killed, the positions re-captured by the regime, and the front collapsed shortly thereafter. It is difficult not to see the same thing playing out now, whether over the course of a few days or a few weeks.

However, today the Turkish military is far more enmeshed in northwest Syria than it was in 2019. Not only does it maintain a ring of observation points around Idlib and bases inside northern Aleppo, it has also served as the main guarantor of the 2020 “ceasefire” since reaching the deal with Russia. That ceasefire is now broken. What Turkey decides to do will almost certainly determine the outcome of this offensive. Fatah Mubin is likely hoping that by achieving massive success early on they can force Turkey’s hand into helping defend the new gains, or perhaps greenlight a SNA offensive from the Afrin axis (which just happens to border the northern side of the FM advance).

Diplomatically, Turkey could work to attain a new deal with Russia that sees this new frontline frozen, or a partial withdraw of FM forces in exchange for an end to the FPV attacks. Militarily, a Turkish-imposed no-fly-zone would go a long way to secure opposition gains, while a Turkish offensive of their own against the joint regime-Kurdish controlled regions north of Aleppo city would force the regime to significantly disperse its forces.

It is clear is that the rules of the last four years have been broken. This is almost certainly Jolani’s core goal in launching the offensive. With Syria ‘frozen’ no more, anyone who shape new facts on the ground has a chance to create a new set of rules going forward.